When I came across the elephant stamp I used for my embossed velvet activity, I also came across some little sponges that I had used to sponge-paint some flowerpots a few years ago. So I thought I'd try sponge-painting for today's elephant.

Natural sponges are multicellular organisms with bodies full of pores and channels, allowing water to circulate through them. Sponges don't have nervous, circulatory or digestive systems, relying instead on a constant flow of water through their bodies to provide them with food and oxygen, while also removing wastes.

Sponges come in many shapes and sizes, all adapted to ensure optimal water flow. Water enters the sponge through a central cavity, deposits nutrients, and leaves through a hole called an osculum. The process functions something like a chimney: water is pulled in from the bottom and is expelled through the top, where waste is washed away by the surrounding currents. Sponges are capable of controlling water flow through various means, and will even close off if there is too much silt in the water.

|

| Yellow tube sponges, Cozumel, Mexico. Source: http://goodnews.ws/blog/2010/02/22/marine-sponges-can-fight-cancer/ |

There are as many as 10,000 known species of sponges, most of which feed on bacteria and small food particles in the water. In food-poor environments, some species of sponge have become carnivores, feeding on tiny crustaceans. Although there are a few freshwater species of sponge, most are saltwater species, and live anywhere from shallow tidal zones to astonishing depths of 8,800 metres (5.5 miles). Sponges in temperate zones live for only a few years, but some tropical and deep-ocean species may live for more than two centuries.

Sponges are found in every part of the world, including polar regions. Most live in calm, clear waters, as sediment tends to block their pores, making it difficult for them to breathe and feed. The great majority of sponges are found on rocks, although some can attach themselves to a sandy floor with a root-like foot. There are more sponges—although fewer species—in temperate zones, likely because there are more predators such as turtles and fish in tropical zones. In polar seas and the deepest oceans, glass sponges are the most common type, as their porous structure enables them to glean nutrients from an otherwise food-poor environment. If a sponge dries out even partially—as, for example, in an aquarium—its pores close, and the sponge begins to starve and suffocate.

|

| Euplectella sp., a deep-ocean glass sponge. http://avernaculararchitecture.blogspot.ca/2009/01/glass-sponge.html |

Very few sponges actually have the soft, fibrous texture we usually associate with sponges. For millennia, humans have harvested these particular species for use in cleaning and padding. By the 1950s, these particular types of sponge had been so heavily overfished that the sponge industry nearly collapsed, and today most sponge-like materials are synthetic. A loofah "sponge" is actually not a sponge at all, but the inner part of a gourd.

In addition to their use by humans, it was recently discovered that bottlenose dolphins also use sponges. In Western Australia's Shark Bay, dolphins have been observed spearing marine sponges with their rostrums, or nose areas. It is thought that the dolphins are using sponges as a type of rostrum-guard when they search for food on the sandy seabed. Known as "sponging", this behaviour has only been observed in Shark Bay, and almost exclusively by females. A 2005 study suggests that mother dolphins have been teaching their daughters to sponge, and that all sponge-users are related, likely making this a recent innovation.

|

| Sponging dolphin, Shark Bay, Australia. Photo: Ewa Krzyszczyk Source: http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/2418/dolphins-use- sponges-catch-fish-study-says |

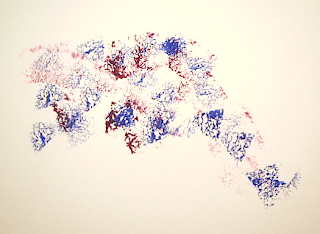

For today's elephant, I had this small selection of sponges, which I opted to use with acrylic paint on a sheet of good-quality bristol board. I'm not sure why I cut these little squares and triangles, given that I don't remember making any kind of regular pattern when I sponge-painted the flowerpots. However, since this is what I had on hand, I decided to limit myself to these particular shapes.

I squeezed blobs of acrylic paint onto an aluminum pie plate, wet the sponges and started painting. I didn't bother drawing anything first, although it might have been easier if I had.

My first effort was a baby elephant. I began with purple, then added blue, then green.

It was beginning to remind me of my experiments with fumage, which wasn't really what I had in mind, but I finished it anyway.

I decided next to make a simple elephant head, following the same colour sequence.

I liked this one better, partly because I had a better feel for the process by now. I layered multiple colours, but also left a lot of white space to give it more dimension and life.

It only took me about a 45 minutes to do both of these, and it was pretty painless. I think I might try to layer in more colour next time, but I'm quite happy with the way they turned out.

Elephant Lore of the Day

At the deservedly renowned David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya, orphaned baby elephants are coaxed into feeding by surrogate mother elephants—in the form of rough, grey blankets hanging from trees. Although to us these blankets look nothing like mother elephants, they actually serve an important purpose.

Baby elephants usually arrive at the orphanage following traumatic rescue from life-and-death situations. Distraught and frightened, they often succumb to pneumonia and gastric infections caused by stress. They also frequently refuse to eat. This presents a particular challenge for the people trying to save them.

It was discovered however, that if a baby elephant feels something similar to the texture of its mother's stomach when it reaches up, it can be coaxed to feed. Encountering large expanses of grey hanging throughout the bush, baby elephants will walk over to the blankets, touching them with the tips of their trunks in curiosity. Reassured by the texture, they will snuggle closer and run their trunks over the surface, just as they would do with their mothers in the wild. It then becomes easier to feed them from a bottle.

The babies remain dependent on the blankets for the first few months, then take the bottle without the blanket, then become tactile with the rest of the herd. When the elephants are between twelve and eighteen months old, they are moved to rehabilitation centres in Kenya's East Tsavo National Park, and are eventually released back into the wild.

To Support Elephant Welfare

World Wildlife Fund

World Society for the Protection of Animals

Elephant sanctuaries (this Wikipedia list allows you to click through to information

on a number of sanctuaries around the world)

Performing Animal Welfare Society

Zoocheck

Bring the Elephant Home

African Wildlife Foundation

Elephants Without Borders

Save the Elephants

International Elephant Foundation Elephant's World (Thailand)

David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Elephant Nature Park (Thailand)

No comments:

Post a Comment